Patient education

Endometrial hyperplasia (and EIN)

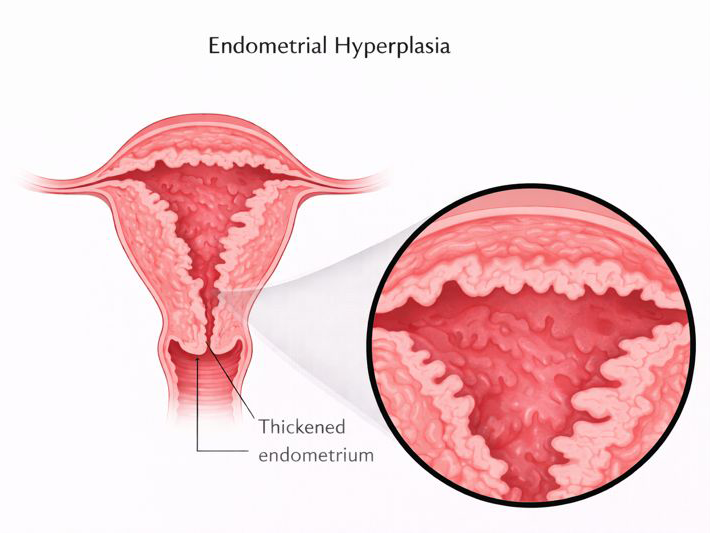

Endometrial hyperplasia means the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) has become thicker than it should be, usually because of hormonal imbalance. Some types are low-risk and often settle with the right treatment. Others (called EIN or “atypical hyperplasia”) need a more careful plan because they can coexist with, or progress to, cancer.

Quick take

If you have abnormal bleeding (especially after menopause), endometrial hyperplasia is one of the conditions we actively rule in or rule out. The key step is usually a lining sample (biopsy), not guesswork.

Tip: “EIN / atypia” is the fork in the road. Management changes because the chance of coexisting cancer is higher, so we plan more carefully.

What it is

The endometrium normally thickens and sheds with your cycle. Hyperplasia happens when the lining is exposed to estrogen for too long without enough progesterone, so it keeps building up instead of shedding normally.

Some patterns are low-risk (“without atypia”). Others are called EIN (endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia) or “atypical hyperplasia” and need a more structured plan.

Symptoms

Most patients present with abnormal uterine bleeding. That can look like heavier periods, bleeding between periods, or any bleeding after menopause.

- Bleeding between periods

- Periods that are heavy or prolonged

- Unpredictable cycles (especially with irregular ovulation)

- Any bleeding after menopause, even spotting

Risk factors (who is higher risk)

Risk factors are mostly about ongoing estrogen exposure without progesterone. This can be from the body (like obesity or ovulatory dysfunction) or from medications/therapies.

- Obesity (estrogen produced in fatty tissue)

- Chronic ovulatory dysfunction (eg PCOS, perimenopause patterns)

- Estrogen exposure from medications/therapies without adequate progesterone

- Tamoxifen use (in selected contexts)

- Hereditary cancer syndromes such as Lynch syndrome or Cowden syndrome

Important: Lynch syndrome and Cowden syndrome significantly increase risk of hyperplasia/EIN and endometrial cancer, so we manage symptoms and screening more proactively.

How it’s diagnosed

Endometrial hyperplasia and EIN are histologic diagnoses. That means we diagnose them by looking at a tissue sample under the microscope (biopsy, D&C, or a specimen from surgery).

Step 1

History + risk check

Bleeding pattern, age/menopause stage, and risk factors that change the urgency of investigation.

Step 2

Ultrasound (sometimes)

In postmenopausal patients, ultrasound may show a thickened/heterogeneous lining, but thickness alone (especially without bleeding) is nonspecific.

Step 3

Endometrial sampling

Biopsy or D&C gives tissue for diagnosis. That’s the decision-maker.

If EIN / atypia is found on an office biopsy, many clinicians perform a D&C to better assess the lining and help exclude a coexisting cancer (sampling volume matters).

Types: “without atypia” vs “EIN”

Broadly, there are two clinically important categories:

Hyperplasia without atypia

Usually hormone-driven thickening without the cellular changes that raise concern. Often treatable with progesterone-based therapy and follow-up.

EIN / atypical hyperplasia

A higher-risk diagnosis. It can coexist with endometrial cancer more often and needs a careful plan (often involving D&C assessment and sometimes hysterectomy, depending on goals and risk).

Even among experts there can be variability in interpreting atypia, which is another reason management is structured and sometimes includes confirmatory sampling.

Cancer risk (in plain language)

Two ideas matter:

- Progression risk: EIN/atypia has a much higher risk of progressing compared with “without atypia”.

- Coexisting cancer: Sometimes cancer is already present but missed on a small sample, which is why further assessment is often recommended when EIN/atypia is diagnosed.

Coexistent endometrial carcinoma may be present in up to 40% of patients with EIN/atypia, and <1% in those without atypia.

Treatment options

Treatment depends on (1) the type (without atypia vs EIN), (2) whether you want future fertility, (3) menopause stage, and (4) your overall risk profile.

Progesterone-based therapy (medical management)

Progesterone helps counterbalance estrogen and can thin the lining. Options include tablets and, in many settings, a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena type IUD), which is often used because it is effective and easy to use.

Procedures / surgery

- D&C (dilation and curettage): sometimes used after an office biopsy showing EIN/atypia to assess more thoroughly.

- Hysterectomy: may be recommended in selected patients, especially after completed family or when risk is higher (this is individualized).

The goal is not “over-treatment”. The goal is choosing the right intensity of care for the specific diagnosis, while keeping fertility goals and safety in mind.

Follow-up & monitoring

Follow-up usually includes repeat sampling at appropriate intervals to confirm the lining has responded and to avoid missing persistent or progressive disease. This is especially important when medical (progesterone-based) management is used.

Some management pathways include maintenance therapy that may be continued for an extended period in selected cases.

FAQ

Can ultrasound diagnose hyperplasia?

Ultrasound can suggest a thickened or heterogeneous lining in postmenopausal patients, but ultrasound criteria are not as definitive for hyperplasia/EIN as they are for some cancer pathways. Tissue diagnosis is usually required.

Are biomarkers part of routine diagnosis?

Some immunohistochemical markers may help in difficult cases, but they are considered experimental and are not routinely performed in standard practice.